‘I’m a pedestrian, nothing more.’

Arthur Rimbaud

There are many ways to take a step. Intrinsic to human experience and natural rhythm, the step is a symbol through which acts—from political transgression to spiritual ascent—can be expressed. We move ‘in step’ with fashion or progress; we take ‘desperate steps’ or steps toward uncertain goals. It is through gradual accumulation that step-by-step advancement may eventually converge to the possibility of sudden revelation—a journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.

Steps place us on the axes of existence, in relation to thresholds. They represent transition between interior and exterior worlds, the private and the public. To ascend or descend is to move through psychological states, memory and dream—through layers of consciousness. In stepping, the body becomes an instrument of knowing as Friedrich Nietzsche insisted in Ecce Homo: ‘Do not believe any idea that was not born in the open air and of free movement—in which the muscles do not also revel.’

What Nietzsche insisted upon bodily, Martin Heidegger pursued as a methodological task. His Schritt zurück (the step back) is a concept that emphasises the importance of affirmatively refraining from familiar frameworks in order to open space for alternative thinking, to rediscover what was leapt over (übersprungen). In doing so, we are able to return to a ground from which we derive our idea of truth, where different modes of cognition still constituted a unity.

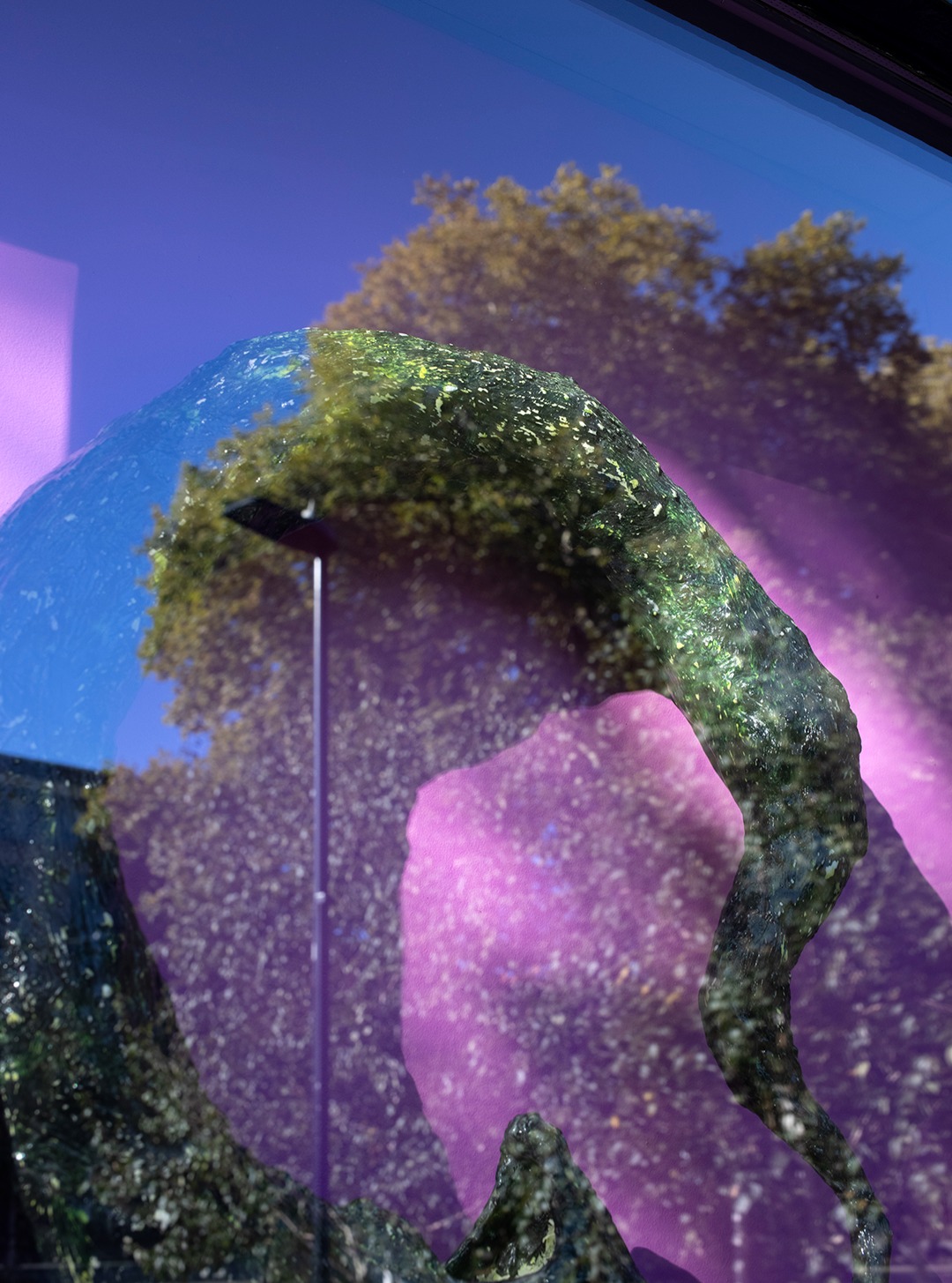

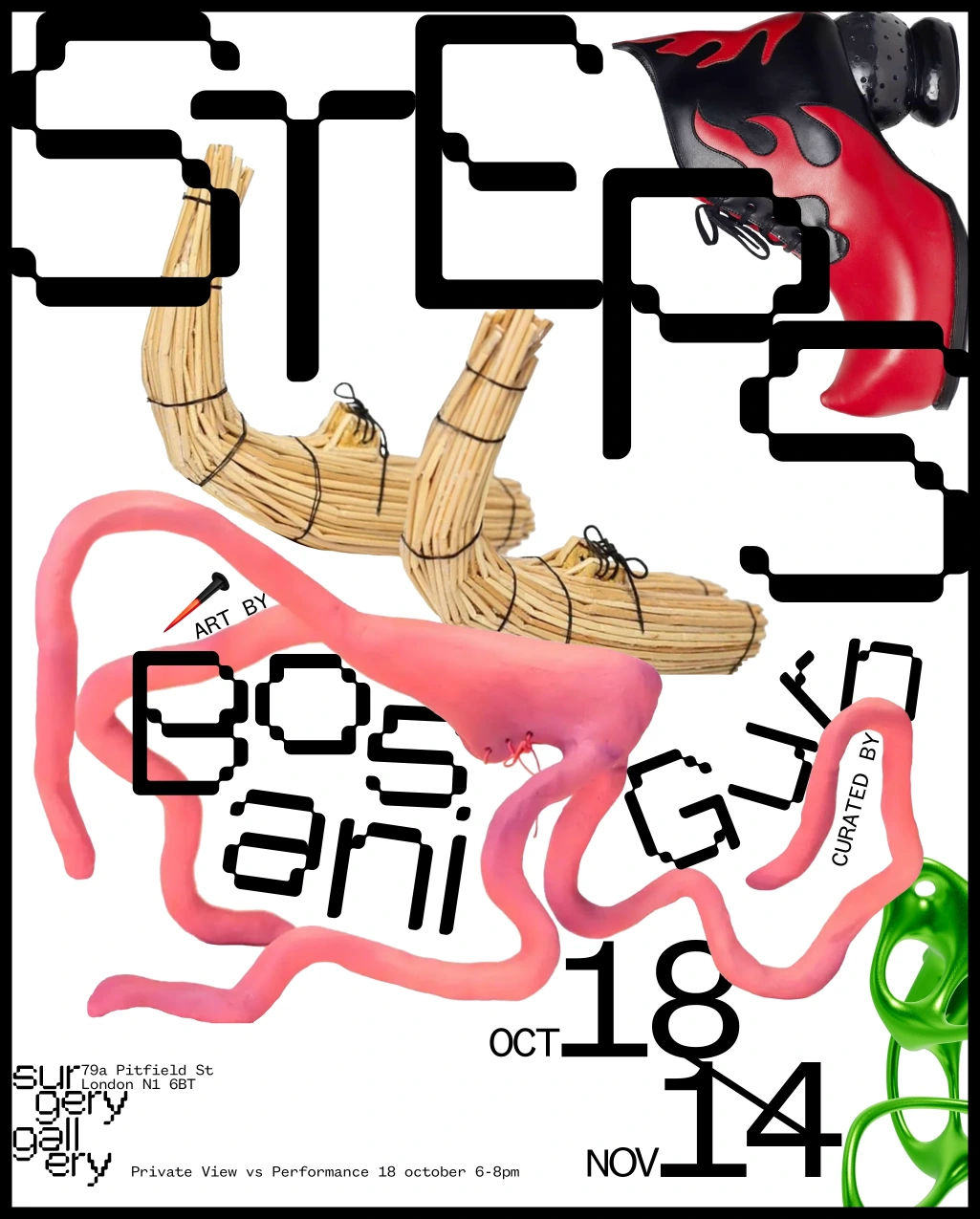

Taking steps can mean escaping identity as fixed category—the constraints of gender, class, or social obligation; movement unmakes what seemed immutable. The technique of detachment animates Luca Bosani’s (b. 1990, they/he) practice, enacted, paradoxically, through surplus. In the objects they create, extravagant ornamentation becomes a queering of the maker's gesture that challenges utilitarian codes—the binary of function versus embellishment—and oversteps the limits of what an object, or a body, is permitted to be.

Bosani’s work goes in unexpected directions and in different ways: stepping back into their family’s lineage of shoemaking and the broader history of craft, they derive new affirmations in both material and social dimensions, examining how we encode gendered economies and how the rhythms these structures impose can separate or unite us as social beings. In attending to the material conditions of stepping, Bosani explores how movements are shaped by invisible architectures of power, and how craft knowledge might be mobilized to reimagine the choreographies of belonging.

If steps can dissolve identity, they can also forge it: walking together produces publics, marching produces movements, synchronized pacing produces ritual and solidarity. Whether collective or solitary, we are all dedicated to making steps, in one direction and another: a first step marks the beginning of individual autonomy; with a misstep, everything can end. The imperative here is not mere forward momentum but generating new strength, pushing while maintaining balance. So it’s with thought. So it’s with art. Each step is the goal.

To step you need to start. The rest is optional.